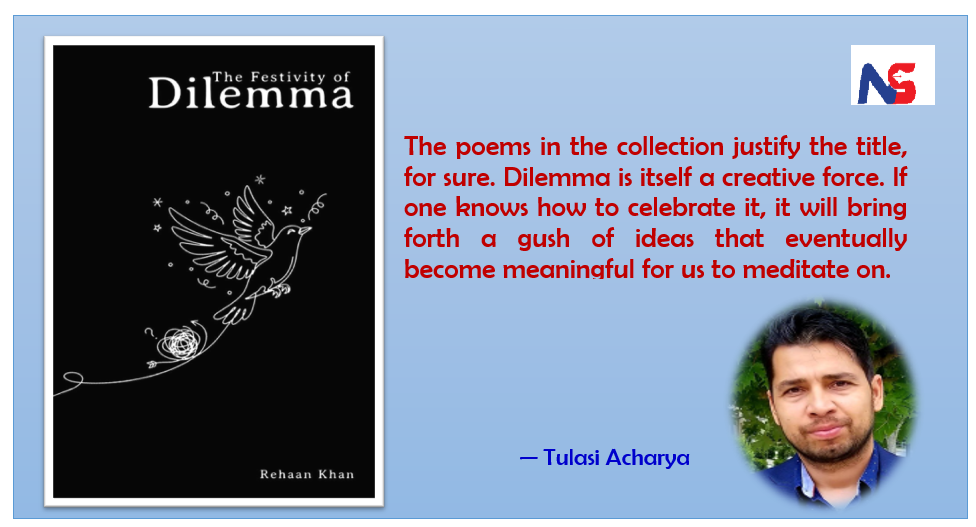

Tulasi Acharya

The Festivity of Dilemma, penned by Rehaan Khan and translated by Mahesh Paudyal, is a collection of thirty-seven poems written in free verse, mostly short in length. You don’t have to be a poetry lover or an avid reader to discern Khan’s poems because the poet picks subjects from our quotidian chores. The poet transforms the insignificant into the significant, the tiny into the big, and the marginalized into the center. Many of the one-word–titled poems, such as “Leaves,” “Dilemma,” “Journey,” “Life,” “Interval,” “Portrait,” “Autism,” “Mother,” “Transit,” and so on, flaunt the poet’s dexterity with simple subjects that we encounter in our everyday lives but often fail to see the significance of. The meditative feel of each poem in the collection qualifies Khan as a promising poet. Even “An Oil Lamp” becomes a topic of a poem, making us conjecture how ordinary a subject the poet could have worked on to speak something extraordinary out of it. This is an example of how poems, being simple and average, without being experimental, touch one’s heart and help others relate to the poet’s experiences in many ways.

The poems in the collection justify the title, for sure. Dilemma is itself a creative force. If one knows how to celebrate it, it will bring forth a gush of ideas that eventually become meaningful for us to meditate on. In one of Khan’s poems entitled “Dilemma,” the speaker is both creative and philosophical simultaneously when they say:

“Worked up with life and trepidations

When I readied myself

To scribble a suicide note

The pen suspended me

And wrote its own suicide note.

I don’t know if the pen is in my favor

Or in favor of life.” (2)

At times, the poems are short, vivid, and very meditative in nature, as when Khan writes: “Never ask me which home I come from / which village is mine / And which place or town I belong to.” (5) There are certain idioms—so lovely and beautiful—that lend credibility to the poems, for example, “curtains of clouds” in the line “their eyes had curtains of clouds” from the poem entitled “Oh My Princess from a Distant Land.” However, this poem, though beautiful and thoughtful, could be made more poetic if it were written this way:

I walk into the woods

Lift some leaves

The wind blows them away

To a fairy land

I wonder

If my princess

Ever sees them stuck

On her window

However, it is true that certain poems are beautiful in their original language, and I could kill their beauty if I translated them into a different one. Paudyal has done a fantastic job by translating the right poems originally written in Nepali. Extremely experienced and well-versed in translation, and himself a writer, critic, and poet, Paudyal’s translation is a charm in this collection, despite some awkward idioms to native speakers’ ears.

There are many moments one can relate to while reading the poems, and that is the power of poetry—or any work of art. Images and metaphors in the poetry repeat, underscoring the importance of birds, branches, people, trees, childhood, memories, festivals, and the like. The tone of some poems is pessimistic and, at times, philosophical and optimistic. The pessimistic tone unsettles me, but the hope that some poems bring does not let the beauty of the collection die. Some lines are nostalgic and vivid, as when the poet writes these lines in the poem entitled

“Dear Dashain”:

“…Those wayside flowers

Chrysanthemums, velvets, and marigolds

That had shed tears at my farewell

That cuckoo, Danphe, munal, and the crows

That had mused of flying with me

Are also waiting for me…” (20)

Similarly, “Childhood Days” asks deep, rhetorical questions for the reader to ponder. The ideas in the poetry continue to linger even after we finish reading them. At times, the lines become poetic and memorable and stay in the reader’s mind. For example, the poet writes:

“…Like a wall clock that suspended its tick-tock

Years ago on the wall of my abandoned house

Like a calendar that still lingers

Even after the year has changed…” (43)

The poetry does not forget to be critical of a selfish society and money-minded people who rip off others for the sake of personal gain or benefit:

“Years ago

Some stakeholders had fixed a dim bulb

On a wooden pole at this spot

The pole survives

The bulb hangs too

But there is no light”

Such lines draw the reader into down-to-earth scenarios through imagery we encounter in everyday life.

Overall, the poems are beautiful and promising. Translation is not an easy task; it is risky, challenging, and highly intellectual, and Paudyal has performed exceptionally well despite minimal awkward phrasing for native speakers and a few typos. There is ample room for these poems to be developmentally edited for greater clarity and grounding. The poet could have used more olfactory and gustatory sensory details, which would have been a feather in the cap. Overall, one can simply enjoy the poems. Kudos to the poet and the translator.